USS SLATER Deep Freeze tours

SLATER Deep Freeze Tours: Winter 2025 – 2026

Monday – Friday: 10 AM & 1 PM

USS SLATER is offering Deep Freeze Tours throughout the winter months when we have historically been closed to the public. These tours cannot be offered as often as our regularly scheduled tours, but they will offer a glimpse of what our volunteers are working on throughout the winter season. The tour length can vary due to your interest and time constraints. The tour could last as long as two hours. We will be flexible with your schedule.

Explore the decks with real-life North Atlantic Convoy conditions!

Realistic expectations:

The entire ship will not be on display. Guns will be covered for the winter and some locations will be closed for the season.

You will still hear the history of the ship, see where the sailors lived, ate, and slept. You’ll hear and see for yourself what our volunteers are working on.

Most of the tour will take place inside the ship, but you should still dress for the weather – as the heat does not reach all spaces equally.

Tickets must be pre-booked and are available through our website. They will not be available for purchase at our office for walk-ins.

If we need to cancel your tour for any reason, (foul weather, lack of tour guide, hazardous conditions of the decks, etc.) we will offer a full refund and let you know via email before 9 AM the day of your tour.

Our Ship’s Store will be open after your tour.

If you have any questions please reach out to Shanna. We look forward to having you aboard!

What is ‘operation deepfreeze’?

The following was written by Gene Spinelli, an Electronics Technician whom served aboard two destroyer escorts during his Deepfreeze deployments. He has created a website dedicated to telling the story of those that served on similar deployments to Antarctica. Read more here.

Before the high-tech days of weather satellites and the Global Positioning System (GPS) aircraft making the journey between Christchurch, New Zealand and the US base in Antarctica at McMurdo, would depend on weather reports and navigational fixes from a weather picket ship deployed in the vicinity of 160 East and 60 South. Both the United Sates and New Zealand navies provided ships for this purpose. The NZ Navy’s participation was between the years 1962 – 1965.

During the years 1957 – 1968, the US Navy deployed Destroyer Escort (DE) class ships for this duty, and the New Zealand Navy provided Loch-class antisubmarine frigates. The US ships were WWII vintage DEs later replaced by Destroyer Escort Radar (DER) class ships. The DERs were WWII EDSALL-class DEs that were converted for radar picket duty in the mid-1950s. Built from 1943 until the end of the war at a cost of a few million dollars, it was never intended for these ships to be in service into the 1970s.

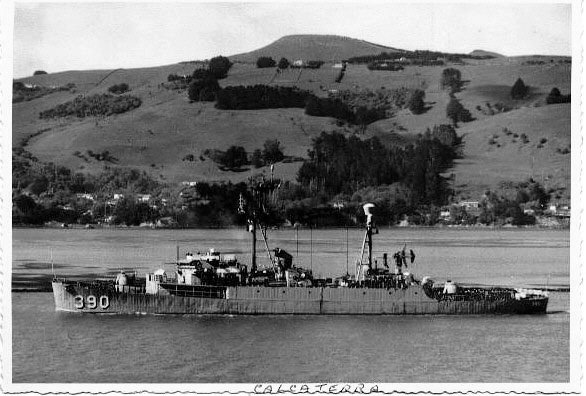

The DERs was easily distinguishable from its original WWII configuration by their unusual architecture including the addition of a second mast, “Tactical Air Navigation” (TACAN) gear, the SPS-8 Height Finding Radar system, and an after-deck house on the 01 level.

The EDSALL-class DEs were selected for conversion because of their Fairbanks Morse diesel engine propulsion system. With a full tank of fuel this configuration could travel many thousands of nautical miles nonstop. It wasn’t the smoothest ride you’d ever experienced, with a displacement of 1,700 tons, 306 feet long, 37 feet at the beam and 14 foot draft, it could have been worse, and during Antarctic storms it was.

In all, 36 EDSALL-class ships were converted to DERs with 8 of them serving as Deep Freeze weather picket ships. Towards the end of WWII 7 BUCKLEY-class DEs were converted to DERs but those earlier conversions were deemed unacceptable for radar picket duty.

During the early Operation Deep Freeze years one US Navy picket ship would be deployed to southern waters. Later in the program the US and New Zealand Navies would alternate their time on station. From 1966 through 1968 the US Navy provided two DERs during each season both being ported in Dunedin, NZ, but I don’t recall at any time both ships being in port at the same time.

While being processed, the Petty Officer of the Watch said “You lucky dog, you’re going on an around the world cruise. CALCATERRA will leave Newport in August for Dunedin, New Zealand, completely circle the earth and return to Newport in May of next year”. I spent one month on Yosemite waiting for CALCATERRA to return from Dog Rocks.

So, at the age of 19 I embarked on a once in a lifetime experience: completely circling the earth twice; transiting the Panama and Suez Canals; being inducted into the Ancient Order of the Deep by crossing the Equator; crossing the International Date Line, the Antarctic Circle, and spending two birthdays in the Southern Ocean.

The journey to Dunedin took about a month. Departing Newport we sailed for the Panama Canal. After a few days at the US Navy base, Balboa, Canal Zone and few days at Callao (Lima) Peru, we began what was to be a 20 day non stop voyage to New Zealand. Because of rough seas along the way the voyage took longer than planned. CALCATERRA arrived at Dunedin on September 21, 1965 with its fuel gauge almost on empty.

After taking on fuel and supplies, we departed Dunedin on September 25th for the New Zealand weather station at Campbell Island. I’d soon learn that part of the routine was to stop at Campbell Island to offload mail and supplies for the handful New Zealand scientists who lived on the island and on the return journey stop again to pick up outgoing mail. Crew members went ashore to tour the weather station and enjoy a beer at the recreation center. After several hours we’d be underway again headed for picket station at 60 South.

I eventually learned that Deepfreeze pickets were an exercise in routine. By the end of my Deepfreeze assignments, I made a total of nine pickets aboard the CALCATERRA and USS THOMAS J. GARY (DER-326). During these pickets the Aerographers would send up at least two weather balloons a day and the Sonarmen would make regular bathythermograph drops, in all sorts of seas and weather.

The weather balloons contained a Radiosonde transmitter which sent various weather measurements back to the ship. As the balloon made its way into the upper atmosphere, the Radarmen, using the SPS 8 height finding radar, would log the balloon’s altitude and direction. The Aerographers would compare the radar tracks to the Radiosonde data, compute the results, and send weather reports to McMurdo and Christchurch. As required, the TACAN beacon would be transmitting navigation information for inbound and outbound aircraft.

Electronics Technicians did not stand underway watches, which probably annoyed those crewmembers who did stand underway watches. The trade-off was we were on call 24 hours a day to handle any failure of the radar or communication systems. During the regular workday we would perform preventive maintenance or make routine general repairs.

While on picket station aboard the CALCATERRA, I was awakened one night by “Spinelli wake up, the 10 is down”. Of course, this meant the AN/SPS-10 surface search radar was not working and the ship was operating blind. All the SPA-8 and SPA-4 repeaters showed the same pattern of pulses which should not have been there. I’d seen this problem once before and went to the transmitter room where I was met by a newly minted Ensign. The ship was surrounded by icebergs without radar, not an enviable place to be. The Ensign was as nervous as one could imagine and he kept asking me how long it would take to repair. I remember saying “10 minutes after I figure out what’s wrong”. He went to the bridge and reported it to the Commanding Officer (CO) while I diagnosed the problem.

The CO, obviously concerned by whatever the Ensign told him, came down to the transmitter room and asked how long until it’s fixed. In the time it took for our nervous Ensign to go to the bridge, update the CO and for CO to come down to the transmitter room I had already replaced the failing part and restored the system to operation.

On another picket aboard the THOMAS J. GARY, I was awakened at about 2AM by those same words “Spinelli wake up, the 10 is down”.

The problem was relatively easy to see; the radar antenna was turning but there was no such indication on any of the repeaters of that rotation. By about 3AM I concluded the problem was either a bad servo at the antenna or a broken cable. The CO came down to CIC and asked for an estimated time to repair. I explained the situation and he said, “The Aerographers tell me the best weather we’re going to have for the next few days is right now”. I immediately knew that meant he wanted me to climb the mast while underway as the ship was pitching and rolling in the cold Antarctic night.

So up the mast I went with some hand tools and my trusty PSM-4 multi-meter. As I recall, the ship was rolling quite a bit and I could only climb as the ship rolled to port. During a port roll my body would be against the ladder, on a starboard roll I’d be hanging off the ladder with my back to the sea. This was a no brainer, only climb on port rolls.

Eventually I arrived at the upper radar platform, strapped myself to the railing and opened the antenna pedestal’s access plate. It took all of 10 seconds to see a broken wire on the servo and another minute or two to make the repair. Back down the mast (on port rolls) fire up the system and watch the smile on the CO’s face.

So, why did the wire break? One year earlier while on picket station at 60 South, a portion of the radar antenna was swept away during an Antarctic storm. A new antenna was shipped to Dunedin and installed by the ship’s ET gang. Apparently, vibration caused the wire to fracture at the servo.

These vintage DERs had a nasty habit of blowing boilers, generators, evaporators, and just about any of that old infrastructure which was never intended to be operational 20+ years after they were built. We were fortunate to have the services of Sims Engineering in Dunedin available. Over the years Ted Sims became proficient at replacing major assemblies by cutting plates from the ship’s hull and using hoists and cranes to remove and replace just about any item that needed attention.

So, what was the most exciting memory from these deployments? There were many, but without question it would be the December 1965 picket at 60 South. We had aboard a reporter/photographer from the Otago Daily Times newspaper. On this picket the CO (Lt. Commander W.C. Earl) performed some amazing feats of ship handing by bringing CALCATERRA alongside icebergs for close inspection. Pictures of these ice capades are available on my web site, referenced below.

During this duty we sailed below the Antarctic Circle and spent Christmas Day at the Balleny Islands. Also on the website is a copy of the newspaper article written by the reporter. While his article is factual it’s clear it was written by someone who had never sailed in the Southern Ocean.

After the March 1968 deployments by CALCATERRA and USS MILLS (DER-383) the weather picket ship program to 60 South was discontinued. Technology finally caught up with the old ships as satellites took over the weather – navigation duties. Of course, a satellite would never be able to assist if an airplane ditched at sea. However, I’m not aware of any situation through 1968, or after, where an aircraft making the journey to and from the ice had to ditch at sea.

Those were amazing years, and to have the opportunity to completely circle the earth on a US Navy ship, twice, would be exciting by anyone’s standard. It was a great experience that influenced me for the next 60 years. Of course, today it’s much more pleasant to travel these long distances on a Boeing Dreamliner.

I built the web site at www.aspen-ridge.net (www.60south.net) in 1998 and have been updating it as people sent me information. My original goal was to consolidate and document the memorabilia I had from those years. What I didn’t realize was the number of people I’d meet along the way also had photographs and documents from those years. Before too long people were sending me their scrapbooks to be scanned and published to the website.

Over the years I’ve met several former shipmates around the US and in New Zealand. I’ve lost track of the number of photographs on the web site; the photographs bring back long forgotten memories. Hopefully, some of you reading this article have been reminded of the excitement of circling the earth, one or more times, on a destroyer escort.

About the author:

Gene Spinelli lives in Tucson, Arizona, his navy enlistment ended in June 1967. Shortly afterwards he joined the IBM Corporation from where he retired after nearly 40 years of service. He spent another 5 years at an IBM/Ricoh joint venture company. Now retired, he and his wife enjoy traveling the world. Gene can be heard on the Amateur Radio bands as K5GS. In 2012 he returned to Campbell Island with a team of Amateur Radio operators.

Deep Freeze Tickets:

$20 per adult (18-64)

$18 per senior or veteran (65+)

$16 per child (6-17)

children 5 and under are free of charge.

In April 1965 as a newly minted Third-Class Electronics Technician (ETR-3) awaiting assignment at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, I was handed orders to the USS CALCATERRA (DER-390) at Newport, Rhode Island. The Chief that handed me the envelope laughed and said, “Do you know what a DER is?” to which I responded “No.” He then explained the life of an east coast DER sailor: depart Newport and sail to the waters around Cuba to sit for 30 days tracking aircraft in and out of Cuba. The picket station was known as “Dog Rocks”.

As I boarded a Greyhound bus for Newport, the bus driver asked what ship I was bound for. After entering the base, he would take you as close as possible to your ship. Only problem was the CALCATERRA sailed for Dog Rocks that morning to relieve another DER that had broken down as they were known to do. I was taken to the USS YOSEMITE (AD-19) and checked in at the Quarterdeck.